- Home

- David Alan Johnson

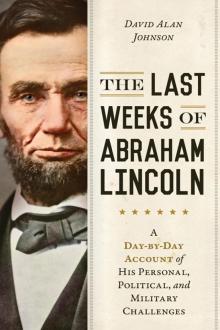

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln Read online

ALSO BY DAVID ALAN JOHNSON

Battle of Wills

Yanks in the RAF

Decided on the Battlefield

Published 2018 by Prometheus Books

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln: A Day-by-Day Account of His Personal, Political, and Military Challenges. Copyright © 2018 by David Alan Johnson. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Cover design by Nicole Sommer-Lecht

Cover image © Alamy Stock Photo

Cover design © Prometheus Books

The internet addresses listed in the text were accurate at the time of publication. The inclusion of a website does not indicate an endorsement by the author or by Prometheus Books, and Prometheus Books does not guarantee the accuracy of the information presented at these sites.

Inquiries should be addressed to

Prometheus Books

59 John Glenn Drive

Amherst, New York 14228

VOICE: 716–691–0133 • FAX: 716–691–0137

WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM

22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Johnson, David, 1950- author.

Title: The last weeks of Abraham Lincoln : A Day-by-Day Account of His Personal, Political, and Military Challenges / by David Alan Johnson.

Description: Amherst, New York : Prometheus Books, 2018. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018019523 (print) | LCCN 2018044028 (ebook) | ISBN 9781633883987 (ebook) | ISBN 9781633883970 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865--Chronology. | Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865--Assassination. | United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Peace--Chronology.

Classification: LCC E457.45 (ebook) | LCC E457.45 .J64 2018 (print) | DDC 973.7092 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019523

Printed in the United States of America

VD1

Acknowledgments

Introduction

March 4, 1865, Saturday: A Sacred Effort

March 5, 1865, Sunday: A Welcome Relief

March 6, 1865, Monday: Inauguration Ball

March 7, 1865, Tuesday: Office Routine

March 8, 1865, Wednesday: Political Affairs

March 9, 1865, Thursday: Communications with General Grant

March 10, 1865, Friday: Day of Rest

March 11 and 12, 1865, Saturday and Sunday: Life and Death Decisions

March 13, 1865, Monday: Not Sick, Just Tired

March 14, 1865, Tuesday: Cabinet Meeting

March 15, 1865, Wednesday: Evening at Grover's Theatre

March 16, 1865, Thursday: Tad

March 17, 1865, Friday: The President Thinks Ahead

March 18 and 19, 1865, Saturday and Sunday: Executive Decisions

March 20, 1865, Monday: City Point

March 21, 1865, Tuesday: Lincoln Decides to Take a Trip

March 22, 1865, Wednesday: A Flattering Letter

March 23, 1865, Thursday: Heading for City Point

March 24, 1865, Friday: Arrival

March 25, 1865, Saturday: Visiting a Battlefield

March 26, 1865, Sunday: The Presidentress

March 27, 1865, Monday: Aboard the River Queen

March 28, 1865, Tuesday: “Let Them All Go”

March 29, 1865, Wednesday: “Your Success Is My Success”

March 30, 1865, Thursday: War Nerves

March 31, 1865, Friday: Much Hard Fighting

April 1, 1865, Saturday: Anxiety at City Point

April 2, 1865, Sunday: Messages for General Grant

April 3, 1865, Monday: “Get Them to Plowing Once”

April 4, 1865, Tuesday: The President Visits Richmond

April 5, 1865, Wednesday: Return to City Point

April 6, 1865, Thursday: Bringing the Fighting to an End

April 7, 1865, Friday: “Let the Thing Be Pressed”

April 8, 1865, Saturday: A Hospital Visit and a Reception

April 9, 1865, Sunday: “Lee Has Surrendered”

April 10, 1865, Monday: Return to the White House

April 11, 1865, Tuesday: A Fair Speech

April 12, 1865, Wednesday: Only a Dream

April 13, 1865, Thursday: “Melancholy Seemed to Be Dripping From Him”

April 14, 1865, Friday: Ford's Theatre

April 15, 1865, Saturday: A New World

Epilogue: “The Loss This Country Has Suffered”

Appendix

Notes

Index

I received a great deal of assistance from librarians and historians in gathering all the material needed to put this book together, and I would like to single out a few individuals who went out of their way to help me out.

I would like to thank Jeffrey Bridgers at the Library of Congress for his assistance with photos.

Dr. James Cornelius of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum was also a great help. I would like to thank him for answering all of my many and persistent questions.

Also, many sincere thanks go out to the staff of the Union, New Jersey, Public Library. Thank you to Laura, Eileen, Denise, Susan, and all of their colleagues for their assistance.

And last, but certainly not least, many thanks to Laura Libby for all of her help and understanding, and for putting up with me once again, as she has done with every one of my other books.

The last six weeks of Abraham Lincoln's life are among the most important and eventful in the history of the United States. Among the events that took place between March 4, 1865, and April 15, 1865, were Lincoln's Second Inauguration as president of the United States, climactic battles leading up to the end of the Civil War, Robert E. Lee's surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, and the assassination of President Lincoln at Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865.

Not every day during the last days of Lincoln's life was eventful. Some were filled with nothing more than the business of politics and of running his office. The president also needed time to recuperate from the strain and tension of the war and spent some days confined to his bedroom. But on March 28, aboard the steamer River Queen, the president met with General Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union forces, General William Tecumseh Sherman, and Admiral David D. Porter, to discuss the prosecution of the war as well as postwar strategy for rebuilding the South. As Carl Sandburg put it, “They were hammering out a national fate.”1 After General Lee's surrender at Appomattox on April 9, Lincoln shifted his thoughts to postwar reunification of the country.

Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address, which he delivered on March 4, 1865, set the tone for how he wanted the war to be fought and what he envisioned for the immediate postwar period. The president wanted a terrible war, a war that would permanently end the rebellion and destroy the armies of the Confederacy, but he also looked forward to a generous peace. “With malice toward none; with charity for all,” he said, “let us strive to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds.”2

But before there could be a magnanimous peace, the war would have to be brought to an end. Not much fighting took place during the early weeks of March 1865. The roads in Virginia were still muddy and unusable from the winter rains, and attacks were limited to skirmishes and contacts between Union and Confederate pickets. General Grant waited for the roads to dry before carr

ying out his spring offensive against General Robert E. Lee and his army. Grant hoped this would be the last campaign of the war. Lincoln was hoping for the same thing.

General Philip Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah had chased Confederate general Jubal Early out of Virginia's Shenandoah Valley and had destroyed most of the farms in the area by late March. General Sherman kept pushing his men through North Carolina toward Virginia, where he hoped to link up with Grant. Grant had not yet begun his campaign against Lee, but the president sent him an order forbidding him from discussing any subject but military matters with General Lee when the war in Virginia came to an end. Specifically, Lincoln told Grant that he was not to discuss or negotiate any political questions. Politics was the domain of President Lincoln himself, not General Grant or any other general.

General Grant's main anxiety was that General Lee and his army would escape from Petersburg one night, before Grant was aware of it. If Lee moved to North Carolina and joined forces with General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, the war would be prolonged for at least another year, possibly longer. Grant did not have the luxury of concerning himself with “political questions.” His first priority was to stop Lee and destroy his army, and think about negotiations after Lee had surrendered.

President Lincoln met with General Grant, as well as General Sherman and Admiral Porter, aboard the River Queen to discuss war strategy. Just as important, at least in Lincoln's point of view, they also talked about rebuilding the country after the war. General Sherman noted that the president's first priority was to end the war as quickly as practicable, but he also saw that Lincoln wanted to show clemency to the South after the fighting ended.

But the war was not over yet. The spring offensive in Virginia was actually begun by Robert E. Lee, not by General Grant. Lee's forces not only captured Fort Stedman on March 25, which was part of Grant's Petersburg defenses, but also threatened to break Grant's siege of Petersburg. Lee's success was only temporary, however. Grant's counterattack forced Lee to abandon both Petersburg and Richmond.

On the afternoon following the Fort Stedman attack, President Lincoln visited the battlefield. The dead and wounded had not yet been removed from the field, and the president saw the fighting from a soldier's viewpoint. The visit made Lincoln even more anxious to end the war than before.

The president's wife, Mary Lincoln, suffered from her own mental strain and nervousness, which added to her husband's anxieties. Mrs. Lincoln had frequently been called “a crazy woman.” Friends and acquaintances knew that she was not well. Mrs. Lincoln was extremely nervous and anxious. Her condition was frequently the cause of awkward scenes. She often perceived slights and offenses where none were intended and flew into embarrassing rages that made her feel humiliated and ashamed afterward. The president was very sympathetic toward Mary and her condition. Friends remarked that his manner toward Mrs. Lincoln was always “gentle and affectionate.” Even though she frequently embarrassed the president with public outbursts, which were directed at him as well as others, Lincoln always remained calm and did his best to keep her calm as well. Mrs. Lincoln's state of mind did nothing to help the president with his own worries and concerns.

The trip on the River Queen seemed to cheer the president and lift his spirits. But with the arrival of spring the war started again, along with all the stress and strain that went with it. President Lincoln was not at ease over the fighting that he knew was to come. A steady rain turned all the roads into quagmires for several days after Fort Stedman. On the last day of March, General Sheridan was turned back by a Confederate attack at a small town called Dinwiddie Court House. On the following day, April 1, Sheridan personally led a charge against the Confederate flank at the Battle of Five Forks.

Five Forks was a Confederate rout. General Grant ordered an attack all along the line, which turned out to be the final assault at Petersburg. Grant sent President Lincoln a telegram to report the success of the attack, telling Lincoln that everything looked highly favorable, which was a gigantic understatement.

By noon on April 2, almost the entire line of Confederate trenches had been overrun. Petersburg itself surrendered on the following day, and General Grant entered the town on horseback. President Lincoln visited Grant in Petersburg; the two of them talked about politics, about the possibility of General Sherman coming north to support Grant, and about showing leniency toward the Confederacy after the war ended. Clemency for the South was an important topic for the president. General Lee was now in full retreat, heading west along the Appomattox River and trying his best to break away from Grant and escape to North Carolina. After about half an hour, the president said goodbye to Grant and left Petersburg. Shortly after Lincoln's departure Grant received word that Richmond had surrendered. He regretted that he had not heard the news while he was still with the president.

General Grant kept the pressure on Lee—“Still plodding along following up Lee,” a Union officer wrote.3 The two armies finally made contact on April 6, at Sayler's Creek. General Lee lost seven thousand men, most of them captured, and suffered another loss at Farmville on the following day. General Grant sent Lee a note, asking him to surrender. Lee declined. The last battle of the war took place at Appomattox Court House on April 9. Federal troops moved in front of Lee—General Sheridan's cavalry, followed by two infantry corps—blocking any further hopes of a Confederate escape. Lee surrendered to Grant on the afternoon of April 9, 1865.

General Grant telegraphed the news of Lee's surrender the same afternoon, and Washington began celebrating that day. The president was as relieved to hear Grant's message as everyone else in Washington and throughout the North. But now that the war was over, Lincoln began making plans for the postwar period and the rebuilding of the South.

Appointing Ulysses S. Grant as general-in-chief was one of Abraham Lincoln's most important decisions as a wartime president, if not the most important decision. It took three years, and a number of disastrous losses by several Union generals, before Lincoln was able to find the man who had the drive and gumption to outfight and outgeneral Robert E. Lee. President Lincoln knew what he wanted, as well as what he needed, in a commanding general, but could not find him until he brought U. S. Grant to Virginia from the west.

Shortly after General Grant received his promotion to lieutenant general, President Lincoln wrote a letter to the general to say that he was confident in his abilities as a commander. He began by saying that he wanted to express his “entire satisfaction” with what General Grant had accomplished up to that point in time, “so far as I understand it.”4 After this opening, he told Grant, “The particulars of your plans I neither know, nor seek to know,” and followed by informing the general that he did not want to “obtrude any constraints or restraints upon you.” Lincoln also complimented General Grant on the fact that he had managed to avoid any battlefield disasters, and invited Grant to contact him if he might think of anything “which is within my power to give.” The president closed his letter of confidence with, “And now with a brave Army, and a just cause, may God sustain you.”

General Grant's reply indicated as much confidence in President Lincoln as Lincoln had shown in him. He wrote that the president's satisfaction with his record so far, along with his confidence in future campaigns, was “acknowledged with pride,” and that he would do his best not to disappoint either the president or the country. The general also said that he had no cause for complaint against either the Lincoln administration or Secretary of War Stanton, and was astonished at the readiness with which everything he had asked for had been given to him. The last sentence of Grant's letter said exactly what President Lincoln wanted to hear: “Should my success be less than I desire and expect, the least I can say is, the fault is not with you.”

General Grant made it clear that his goal was precisely the same as President Lincoln's: to win the war. He was not going to complain or find fault or make excuses for himself, the way past commanding generals had done. Lincoln realized th

at Grant had the ability and the single-mindedness to take charge of the army himself, and he would not blame the president for any of his failures. The president had complete faith in his newly appointed commander in chief. If Grant could go to Virginia and accomplish the same things he had accomplished at Shiloh, Fort Donelson, and Vicksburg, Lincoln was not going to worry about how he planned to go about it.

The stresses and strains of being a wartime president and overall commander had finally ended for Lincoln, but he was about to find out that being a peacetime president came with its own set of problems and anxieties. Lincoln's policy of leniency toward the South did not make him very popular with many Northerners, including members of his own party. The Radical Republicans had no use for either Lincoln or his program for clemency. They wanted to hang Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and all other high-ranking Confederates, and punish the seceded Confederates for treason.

But the president was not all that concerned with the Radical Republicans or with their opinion regarding his outlook for the postwar United States. He was just as unscrupulous as any of the Radicals and was determined to do anything that needed to be done to push his postwar programs for reunification through Congress.

The president had every confidence in himself and in his ability to carry out his agenda for reunification. But on the night of April 14, 1865, he was shot by John Wilkes Booth, a Southern firebrand who wanted to do something “heroic” for the South. Abraham Lincoln died early on the following morning.

Lincoln's death ended his plan for a magnanimous peace. He wanted the reconstruction of the former Confederate states to be generous and lenient. Instead, “Reconstruction” would come to mean just the opposite—vengeance toward the South and corruption by Carpetbaggers and vindictive politicians. Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, along with the Radical Republicans, carried out their own program, which was to treat the seceded states as traitors and to punish them accordingly. The United States evolved into a different country because Abraham Lincoln was not able to finish his second term or carry out his postwar program for rebuilding and reuniting the country.

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln