- Home

- David Alan Johnson

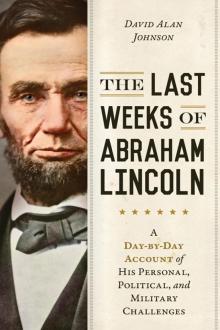

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln Page 2

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln Read online

Page 2

According to custom, the president always traveled from the White House to his inauguration in a shiny carriage, as part of the inauguration parade. The inauguration parade traditionally consisted of floats, marching bands, marching soldiers, and the president's carriage, accompanied by a phalanx of marshals. On the morning of March 4, 1865, Grand Marshal Ward Lamon, who knew Lincoln from the days when they both lived in Illinois, drove to the White House to escort his old friend to the ceremony at the Capitol Building. The pre-inaugural festivities were already in the process of being organized, and Marshal Lamon wanted to make certain that the president would not be late for his own parade.

But when he arrived at the White House, Lamon was informed that the president had already left for the Capitol. He had some work to do, some bills to sign, and decided to take care of these routine details before going off to his inauguration. As far as Lincoln was concerned, the morning of March 4, 1865, was just an ordinary working morning.

Actually, President Lincoln was not as casual about the day as he seemed to be. He knew that he was lucky to be going to his own inauguration that afternoon and was very much aware that he had come perilously close to losing last November's election. Abraham Lincoln nearly did not have a second term to look forward to. During the previous summer, it looked as though he was not going to win the election, and that his rival, George B. McClellan, would be sworn in as president. At the time, General Ulysses S. Grant was deadlocked with General Robert E. Lee at Petersburg, about twenty miles south of Richmond, and General William Tecumseh Sherman had stalled north of Atlanta, Georgia. At least this was what voters in the North were reading in their newspapers. The Democrats were saying that the war was a total failure, and the public listened and believed. “You think I don't know I am going to be beaten,” Lincoln said, “but I do and unless some great change takes place badly beaten.”1

The great change that Lincoln was hoping for took place in September, when General Sherman captured Atlanta. After the fall of Atlanta, which was one of the turning points of the war, public opinion immediately turned in Lincoln's favor. On Election Day, November 8, 1864, voters sent Lincoln back to the White House for four more years. But if it had not been for General Sherman, Lincoln realized that he would only have been in Washington long enough to watch President-Elect McClellan take the oath of office, and that he would have been on his way back home to Springfield, Illinois, immediately after the ceremony. Lincoln was happy and relieved that he would be commander in chief during the last days of the war instead of George B. McClellan.

“The city is quite full of people,” Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote in his diary on the previous day, March 3, 1865, in a staggering understatement.2 Abraham Lincoln's second inauguration had certainly filled Washington, DC, with people—it was overcrowded, jammed, and congested. All the hotels in town were cram-packed. Every nook, cranny, and cubbyhole had been turned into a sleeping space. The Willard, Washington's grandest and most fashionable hotel, even had cots set out in the halls as well as in the parlors, the ballrooms, and in all the public rooms. Everyone wanted to see President Lincoln take his oath of office, or at least wanted to be able to say that they had been in Washington when the great event took place.

But not everybody in Washington had come to wish the president well. “General Halleck has apprehensions that there may be mischief,” Gideon Welles went on to remark, with some apprehensions of his own. “I do not participate in these fears,” Secretary Welles wrote, “and yet I will not say that it is not prudent to guard against contingencies.”3 Major General Henry W. Halleck was chief of staff. Although his headquarters were in Washington, General Halleck was responsible for the administration of the entire United States Army. He was also very concerned with the safety and well-being of the president. It would not look good if anything happened to the president when the chief of staff was in town, especially on Inauguration Day.

Actually, General Halleck's concerns over the president's safety were more than justifiable, and they were not just self-serving. Along with the flood of tourists and sightseers that had come for the inauguration, there were also more than a few malcontents and Confederate sympathizers in town. Many of these individuals hated the president and wanted to see him dead—they blamed Lincoln for the fact that the South was now on the brink of losing all hope for independence. One such person was a twenty-six-year-old actor from Maryland named John Wilkes Booth.

President Lincoln was not at all concerned with security or with his own safety on the morning of his second inauguration; he was too busy signing bills in a room of the Senate wing. Outside the Capitol, the weather was cold, rainy, and generally miserable. The inauguration parade, minus the president, slowly made its way along Pennsylvania Avenue in spite of the weather, and also in spite of the fact that the steady rain had turned all the streets into rivers of mud. The mud was several inches thick in places and sometimes brought the parade to a complete stop—the marching soldiers and parading horses and patriotic floats sank into the goo and stayed there until they could be extracted from their predicament.

By about noon, Lincoln finished his bill-signing tasks and began walking toward the Senate Chamber. The inauguration was to have been held outside, in front of the Capitol Building, but, because the weather would not cooperate, the ceremony was moved inside. At 11:45, all the government officials began making their way into the Senate Chamber. Hannibal Hamlin, the departing vice-president, and Andrew Johnson, the incoming vice-president elect, filed in together.

Vice-President Hamlin opened the proceedings with a short farewell speech, in which he thanked everyone present for their kindness and consideration during the past four years. It was a routine address; not many of the attendees paid much attention to it. Secretary of State William Seward, along with other members of the president's cabinet, arrived to take their seats while Vice-President Hamlin was in the middle of it. This distracted everyone in the room, including Hamlin, who stopped speaking until all the men were seated.

After all the cabinet members had made their way into the Senate Chamber, the justices of the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, filed in and sat down. While this was going on, a group of women in the visitor's gallery kept up a steady stream of chattering and laughing, paying no attention to either Hamlin or what he was saying. Vice-President Hamlin asked them to stop, but they paid no attention to him and kept on talking.

Hamlin had not been very happy during his four years in office, and he did not have a very high opinion of the office of the vice-president in general. As far as he was concerned, the vice-president had no power, no influence, and no respect. The way he was being treated while he was giving his farewell speech only reinforced his low opinion of the position. He did not even have the authority to make a bunch of talkative women shut their mouths.

In spite of all the distractions, the vice-president kept on speaking. No sooner had he restarted his speech than the president's wife, Mary Lincoln, entered the chamber and took her seat in the diplomat's gallery, causing another distraction. This little comedy of errors ended when Vice-President Hamlin finally reached the end of his address. As he read his final lines, guests were still entering the Senate Chamber.

After Hamlin finished, President Lincoln entered the chamber and sat down in the front row—he was a few minutes late, but at least he did not interrupt Hamlin's speech. But Hannibal Hamlin's farewell address was only a minor fiasco. It was about to be followed by a much larger one—Vice-President Andrew Johnson's inaugural address.

Earlier that day, Johnson had complained to Hannibal Hamlin that he did not feel well, and that he should not even be in Washington. He was still recovering from an attack of typhoid fever and had asked Lincoln for permission to take the oath of office at his home in Nashville, Tennessee. But the president wanted his running mate in town for the ceremony, so Johnson obligingly made the trip to Washington.

On the morning of the inauguration, Johnson wa

s still feeling the effects of his illness. When he arrived at Vice-President Hamlin's office, someone brought him a large, tumbler-sized glass of whisky, which was supposed to steady his nerves as well as lessen any lingering effects of the fever. Before leaving for the Senate Chamber, Johnson had another large whisky. According to some accounts, he also had a third. By the time he made his way into the Senate Chamber and onto the rostrum to begin his speech, Andrew Johnson was absolutely and thoroughly drunk. He was not falling-down drunk, but he had enough whisky in him to slur his speech and interfere with his reflexes. Everyone in the chamber, including the president, could not help but notice Johnson's condition.

As he stood in front of a Senate Chamber that was filled to capacity, Johnson began his rambling address by reminding Secretary Seward, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and the Secretary of the Navy (he could not remember Gideon Welles's name) that they derived their power and authority from the people, and not from President Lincoln—apparently, he thought this was a new and revolutionary idea. His voice was raspy and unsteady. He was obviously under the influence. Secretary Welles turned to Stanton, who was sitting just to his right, and said, “Johnson is either drunk or crazy.” Stanton agreed. “There is evidently something wrong,” he said.

“The Vice President made a rambling and strange harangue, which was listened to with pain and mortification by all his friends,” Secretary Welles wrote in his diary. “My impression was that he was under the influence of stimulants, yet I know not that he drinks.” Welles remembered that Johnson had been “sick and feeble, perhaps he may have taken medicine or stimulants…. Whatever the cause, it was all in very bad taste.”4

Everybody present, including all the attendees in the chamber, were stunned by Johnson's performance. A reporter from the New York Herald commented that Andrew Johnson's address was “remarkable only for its incoherence, which brought a blush to the cheek of every senator and official of the government.”5 Vice-President Hamlin tried to catch Johnson's attention by tugging on his coattails, but the vice-president elect kept rattling on in spite of all attempts to stop him. Johnson's speech was supposed to last six or seven minutes; it went on for seventeen.

President Lincoln was as embarrassed as everyone else by the spectacle Johnson was making of himself. He sat with his head down, staring at his shoes, not able even to look at his new vice-president. Johnson eventually did stop speaking, either because Hannibal Hamlin's coat tugging finally caught his attention or because he ran out of breath.

When it became evident that Johnson had reached the end of what the New York World called his “incoherent address,”6 the clerk arrived with a Bible, and the oath of office was administered. Johnson took the oath in a very loud, raspy voice, gave the book a very wet kiss, and sat down. President Lincoln and everyone else present seemed relieved that the incident had ended.

The rain had stopped by this time—it ended at around 11:40, according to most accounts. The sky was still dark and overcast, but at least it was no longer raining. Arrangements were quickly made to continue the inauguration ceremony outside the building, where many more people could see and hear the president give his inaugural address. Lincoln, Johnson, and all the other dignitaries were escorted out of the building to a wooden platform in front of the Capitol. As he made his way out of the building with the rest of the procession, President Lincoln told one of the marshals that Johnson must not be allowed to speak again. It was bad enough that he made a fool of himself within the confines of the Senate Chamber. Lincoln did not want his vice-president, who had now been sworn in, to repeat his performance in front of thousands of people.

As soon as he stepped outside, onto the platform, Lincoln was struck by the size of the crowd that had come to see and hear him. The New York Times called the gathering “a grand crush.”7 A good many soldiers were among those present. Some had come from nearby camps; others were convalescing patients in Washington hospitals. As soon as the president came into view, the “exceedingly large” mass of people began shouting and applauding, and continued their applause as a military band played “Hail to the Chief.”8

At the precise moment when Lincoln began walking toward the rostrum, the sun broke through the clouds. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase thought the sudden burst of sunshine must be a favorable omen. The sergeant at arms of the Senate had already signaled the crowd to quiet down.

At six feet, four inches tall, the president towered above most of those around him. The fact that he was also very thin, and has been diplomatically described as gaunt, made him appear even taller. He was fifty-six years old, but many of his friends and acquaintances thought he looked much older. One of the president's aides, John Hay, observed that Lincoln had changed a great deal during the past four years, and that he was very different from the vigorous and active president-elect of 1861. Mary Lincoln thought that her husband looked tired and careworn. The war had certainly taken its toll. Four years of constant stress and strain had turned Abraham Lincoln into a worn and weary old man.

When the president arrived at the rostrum, he put on his steel-rimmed glasses and looked down at his inaugural address. The speech was in type—not handwritten—and was arranged in two columns on a single sheet of paper. After a moment, he began reading.

“Fellow countrymen,” he said. “At this second appearing to take the oath of the presidential office, there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first.” His first inaugural address was certainly a very different speech than the one he was about to give. On March 4, 1861, Lincoln had asked the South to reconcile their differences with the North and to do everything possible to avoid going to war. But exactly four years later, the Confederacy was on the verge of losing the war that Lincoln had hoped so desperately to avoid.9

“The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to public as to myself; and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.” The progress of Federal arms certainly was encouraging. By the spring of 1865, it was evident to anyone with a realistic eye to the future that the end of the war was in sight. Congress had already begun making plans for peacetime activities, discussing items that included the completion of the Pacific railroad, the resettlement of Indian tribes, and the availability of land for settlement in the West. The end of the war definitely seemed to be within reach. The phrase “after the war” began entering into conversations.

Lincoln next returned to another subject from his first inaugural address, reminding the audience that “four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil-war. All dreaded it—all sought to avert it.” The first address was “devoted altogether to saving the Union without war.” Preserving the Union was the first priority. “Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.” Now the war was almost over, and the president had other things to talk about.

The next paragraph of the speech addressed one of the most important items on the president's agenda for the future of the country: the subject of slavery. “One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest.” President Lincoln elected not to mention the economic reasons for the split behind the North and South, which were just as responsible for the war as slavery. The two sides had treated each other as separate countries long before Fort Sumter—the industrial North and the agricultural South disagreed with each other over taxes and tariffs and imports since the beginning of the republic. The differences of opinion between North and South were not just over slavery.

“All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; wh

ile the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.” This section of the address referred to Lincoln's own expressed interest to prohibit the expansion of slavery in the territories and in other sections of the country, but not to abolish it in the South. Lincoln was well aware that his Emancipation Proclamation had not freed any slaves. The “colored slaves” who lived in the seceded Southern states were beyond his jurisdiction and were still being bought and sold as if the Emancipation Proclamation did not exist.

“Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease.” This was absolutely true. In the days immediately following Fort Sumter, both sides thought that the fighting would be over by Christmas. “Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged.”

The president used the same Bible image of eating bread earned by the toil and sweat of others—which is based on a passage from the book of Genesis—in a debate with Stephen Douglas in 1858. It was just as effective in 1865 as it had been seven years earlier.

Lincoln continued with the use of Bible imagery, this time quoting from the book of Matthew: “Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” A good many blacks were in the audience, including members of a lodge that called itself the African American Odd Fellows. They repeated “’bress de Lord’ in a low murmur at the end of every sentence,” according to the New York Herald.10

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln

The Last Weeks of Abraham Lincoln